Charles Monkhouse is an artist, curator, and lecturer. He works in rural and public spaces to create permanent installations and temporary light works. His work responds to and finds its meaning in its context and location, and often works with local stakeholders – including English Heritage, National Trust, the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site, and Peak District National Park Authority – who inform and enrich the final outcomes. Teaching has always been part of his practice. He was a founding member and later Chair of Arts in the Peak and for a short while Chair of the Trustees for the LEVEL Centre in Rowsley. He continues to work on small projects with local schools and communities.

See more of Charles’ work on his website.

Where are you based?

I moved to Middleton by Youlgrave in 1992 and have a studio nearby. But I trace my interest in landscape and light at night to the Lake District where I have stayed since a child. Many of my lightworks have been produced in Cumbria.

Describe your practice for us

I am an artist working in rural and public spaces to create permanent installations and temporary light works.

The permanent installations are developed with surrounding communities. So, Sites of Meaning, which marked the seventeen entrances to Middleton and Smerrill, was created with local parishioners while in Companion Stones, poets and artists of the Peak District paired historic guide stoops in Derbyshire with contemporary sculptures. Both projects gave a contemporary voice to communities within and around a National Park that emphasises an agenda to preserve its past rather than celebrate the present.

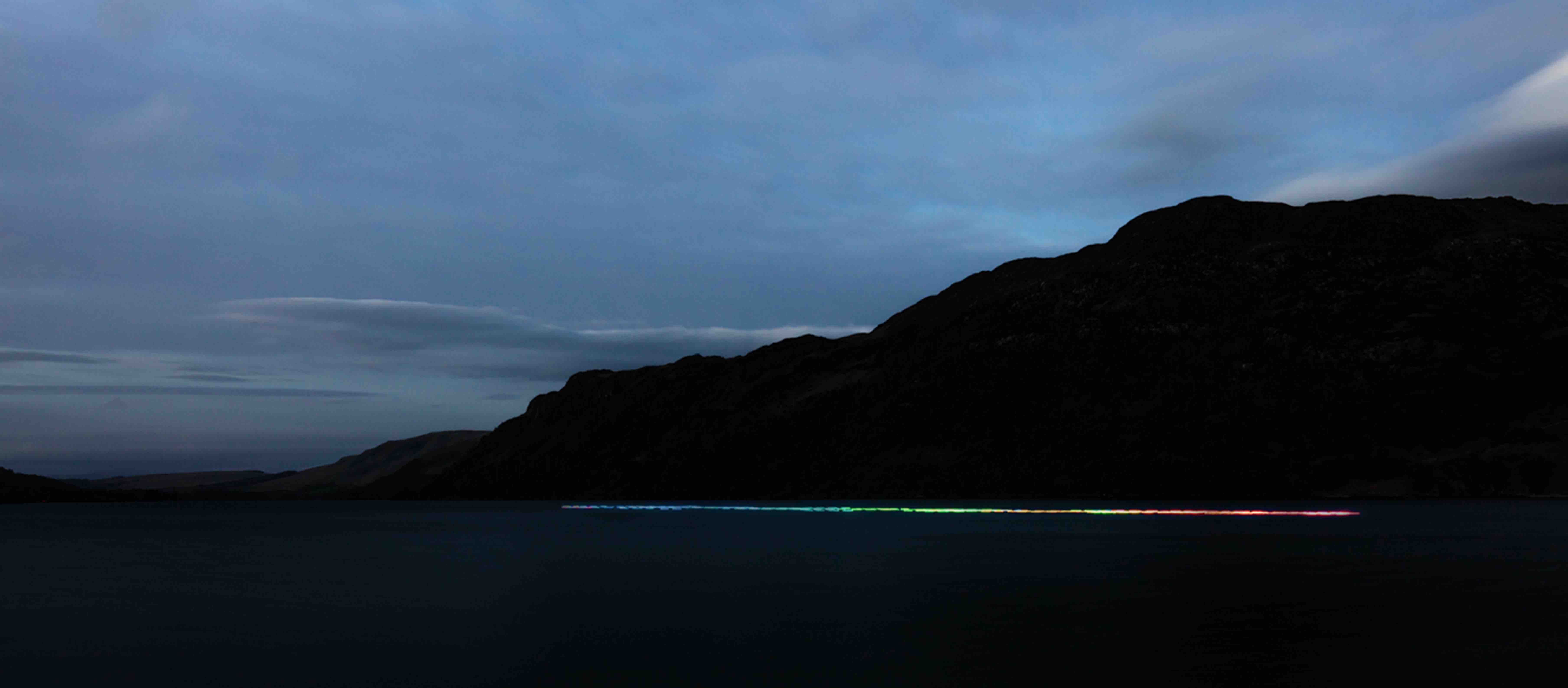

The light works explore and articulate space on buildings and in landscapes, operating under the cover of dark, revealing what is hidden by the light of day. Programmable LEDs play an increasingly important role in this work allowing GPS synchronised installations across large landscapes. Many of these installations have involved local communities in building, installing or shepherding.

Other projects experiment with different types of light. Brocken Spectre with its interplay between light and mist, places an iridescent glory around the shadow of the viewer’s head and was developed for sacred spaces. And recently I have worked on large arrays of LEDs to create beating and pulsating fields of colour.

How long have you been practising and by what route did you come to your practice?

School, PreDip (Foundation), DipAD, Exeter Fellowship and straight into practice and teaching. I count my practice from the first sculpture made during my Foundation course, so 52 years.

After studying at Sheffield and Hornsey, and a fellowship and teaching at Exeter, he started work at Chesterfield. Art colleges were then thriving creative communities providing support, time and an expectation of personal practice. But teaching is part of my practice and although I later reduced my time at Chesterfield to concentrate on my own projects, I now work at Sheffield Hallam and teaching remains an important in my career.

My early practice, sculpture and drawing, was gallery and exhibition based. I showed in polytechnic and university galleries before developing Limits of my Language, a meditation on Meccano, that toured public galleries. Moving to the Peak District precipitated a change to working in the rural landscape and public spaces, the use of light as a medium and the engagement of local communities in the work.

My first community based project was Sites of Meaning (1999-2006) followed by Companion Stones (2008-2010). I started working with light in 2000 but the first significant installations were Evening Glory (2005) and Double Negative (2007) for Steve Messam’s Fred Festivals in Cumbria. Since then I’ve produced light installations nearly every year including Derwent Pulse (2014) and Brocken Spectre at Rievaulx Abbey (2017). Over the past year I’ve explored programming large arrays of LEDs and currently have an installation in the Buxton Pump Room.

You’ve said of your work that it responds to and finds its meaning in its context and location, so is it the idea or location that is the initial motivation for a new work?

I’ve just had a year in my studio experimenting and developing LED work. It’s been good fun and a lot of progress was made, but at the same time it felt a bit empty. Then suddenly a commission arrived with all the excitement, uncertainty and hassle of a short deadline. Wonderful. I don’t want to make work for myself.

Most work is triggered by commissions or by approaching partners to engage in my initiatives. These have included English Heritage, the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site, Peak District National Park Authority and the National Trust.

Your work often results in ambitious interventions in the natural environment, to what extent are you physically involved in their installation, and what can that involve? And do you work with fabricators?

I probably should have used more fabricators and programmers in my work, but I’ve always wanted to have a good understanding of what’s going on and the potential of processes and technology.

But I do work with others in teams and as partners, in developing or delivering projects. In Derwent Pulse the microprocessors that control the beating light spheres were developed with Derby Makers, and the delivery of the project, including shepherding, workshops and documentation, employed 20 people plus volunteers and members of partner organisations.

And Brocken Spectre had a long development programme with photographer Carl Whitham and correspondence with atmospheric optics expert Les Cowley. But its implementation at Rievaulx engaged writers, sound artists, musicians, partnered by the English Heritage Events Team and again, a strong band of volunteers.

Tell us about your approach to working with the public agencies that are often involved in your projects, and how you manage the multiple agendas that these stakeholders bring to them.

My first landscape works, Sites of Meaning in the Peak District and Evening Glory in the Lake District, taught me the importance of positive and proactive relationships with landowners, authorities and communities. So, for instance, Companion Stones was delivered in partnership with the Peak District National Park Authority and Brocken Spectre in a partnership with English Heritage. The partnerships made the work possible.

Multiple agendas are rarely a problem, indeed engaging with partners openly becomes part of the learning and creative process and leads to richer outcomes. Even on small temporary installations, working with local schools and communities can inform, facilitate and validate an installation.

What have been your biggest achievements since establishing your practice?

Occasionally I’m taken by surprised at the unexpected in my work: the scale of Evening Glory on the Old Man of Coniston, the excitement of 1000 people arriving at Chatsworth for Derwent Pulse, the 12 Companion Stones arriving at the Moorland Centre in Edale, the beauty of the glories as we developed Brocken Spectre. But these are just fleeting moments.

Brocken Spectre, inspired by my parents’ experience in 1964 and rekindled by my own mountain walking, has been in my mind most of my life. After two intense periods of development it was shown Rievaulx Abbey. In the right conditions Brocken Spectre is magnificent but struggles with bad weather, so I expect to revisit it again soon.

So to answer, Brocken Spectre. And getting the 40 sculptures of Sites of Meaning and Companion Stones sited across the Peak District.

What have been the biggest challenges to your practice?

I find most projects are a physical and mental challenge. Installations are leaps into the void; many things can go wrong and there’s no guarantee of success. Usually there’s no rehearsal to make corrections. I often wake worrying about the current project but once I’m engaged in the studio or on site everything is possible again. And the weather. Derwent Pulse visited 17 locations along the Derwent. We were really lucky that only one night was ruined by a ghastly upriver wind.

What is the most interesting or inspiring thing you have seen or been to recently, and why?

It’s a book that has had the biggest impact on me during the past year – Richard Powers’ The Overstory. Loosely based on guerrilla groups that championed the giant sequoias against logging companies in the ‘Redwood Summer’ of 1990, the story explores the relationship between trees and humans. Talking about the book, Powers says “Environmentalism is still under the umbrella of a kind of humanism: we say we should manage our resources better. What I was taking seriously for the first time in this book was: they’re not our resources; and we won’t be well until we realise that.” The book reframes the story away from our human project. What we should be doing, Powers says, is ask what Life requires from us. I am still digesting this in my life and my practice.

Which other artists’ work do you admire, and why?

At Sheffield, I’ve been giving lectures on cultural movements. So, returning to the Renaissance I remember how much I enjoy early Florentine painting: Fra Angelico, Andrea de Mantegna, Sandro Botticelli and Piero Della Francesca. There is an almost minimalist simplicity and honesty in their work. Which is strange because when I talk about late Modernism, it’s the bold, ground breaking Americans who grab my attention: Bob Morris and Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, Dan Flavin and James Turrell.

Where do you see your work in the next 5 years?

As a student I knew art would be my life but had no idea what I’d be doing in the next 5 years let alone the next 50. And I still don’t know what I’ll be doing in 5 years except I’ll be doing it

Who would you most like to have visit your studio?

It seems a bit obvious really, but I’d like to have a conversation with James Turrell. Not only because we share a common medium but because we share a common faith. I would like to know more how Quakerism has influenced his practice.

Where can we see your work? Do you have any upcoming exhibitions, events or projects?

Passage in the Buxton Pump Room will have finished by the time this is published. But the 40 sculptures of Sites of Meaning and Companions Stones, combining the work of many residents, poets and sculptors are spread across the Derbyshire Peak. Their locations are detailed on the websites.

Charles was interviewed in February 2020.

All the images are by and courtesy of the artist.