David Ainley studied fine art and ceramics at Derby College of Art and art education at Manchester College of Art/University of Manchester. He was a member and secretary of the Derby Group of Artists 1962-1969 and was invited to become a member of The Midland Group of Artists in Nottingham in 1969, where he was involved in fine art, photography and performance committees. In 1976 he was a founding member of the company set up to manage the transfer of the Midland Group Gallery to The Lace Market. He was Master in Charge of Art at the Joseph Wright Secondary School of Art in Derby (1964-66) and then (1966-1969) was Head of Art at The Herbert Strutt Grammar School, Belper when he also began part-time teaching for The University of Nottingham and the WEA (Workers’ Educational Association). He became Senior Lecturer and Head of Art at Matlock College of Education where, in addition to teacher training he was involved in the development of combined studies degrees. Eventually the college formed a part of the University of Derby where he taught until 1993. He continued part-time lecturing in fine art practice and theory at the University of Nottingham until 2016 where he took a major role in the unique dedicated part-time BA (Hons) Fine Art. He was a tutor on British Council International Summer Schools Landscape and Literature and for NATFHE directed a major national conference Art, Leisure, Education & Purpose in the 1980s. He has lectured widely in fine art departments across the UK, sometimes on materials and techniques for Winsor & Newton & Liquitex (2001-05).

Since his first solo exhibition at Ikon, Birmingham (1966) his work has featured in many one-person shows including Extractive Industry, Westminster Art Reference Library (2017), London Art Fair (2016), Encounters, Southwell Minster (2012), Reservoirs of Darkness, Nottingham (2010). He was shortlisted for the Jerwood Drawing Prize (2000,2005,2017) and won the Derby City Open Exhibition (2004). Numerous other exhibitions include INGDiscerning Eye (2012), Contemporary British Abstraction, London (2015), Contemporary Masters from Britain at Yantai Art Museum & Jiangsu Art Gallery, Nanjing (2017-2018), Made in Britain: 82 Painters of the 21st Century, National Museum, Gdansk, Poland (2019). He was a member of The Research Group for Artists Publications (RGAP). In 2014 he was invited to join Contemporary British Painting and for some years served on the committee. Entry in: Buckman, D (1998 & 2006) Artists in Britain since 1945.

Where are you based?

I work from my studio at home on a hillside above Wirksworth, Derbyshire, in a landscape that has a history of lead mining and quarrying for limestone and gritstone.

Describe your practice for us

My statement that “I have sought to make of Minimalism an art that is as multi-layered in content as are its sources of reference” reflects the basis of my concerns. The seeming simplicity of form and colour in my paintings belies extensive research in the history and practice of painting and investigation of characteristics of place and landscape. From Minimalism, apart from the beauty, elegant simplicity and clarity of the best works, I have a particular engagement with the monochrome and with systems and aspects of process and conceptual art some of which involve lengthy procedures. I think of my approach as involving a distillation of ideas that become embodied in objects that, given attention and time, begin to reveal the history of their making. In turn that opens up layers of content. I like the poet Lorine Niedecker’s concept of ‘condensery’. I have since 1995 made paintings and drawings that question the aestheticization of landscape as scenery and its conventions of perception and representation. Mined and quarried places are the subject of reflections on histories of human labour often hidden from admirers of the spectacular and picturesque in landscape.

How long have you been practising and by what route did you come to your practice?

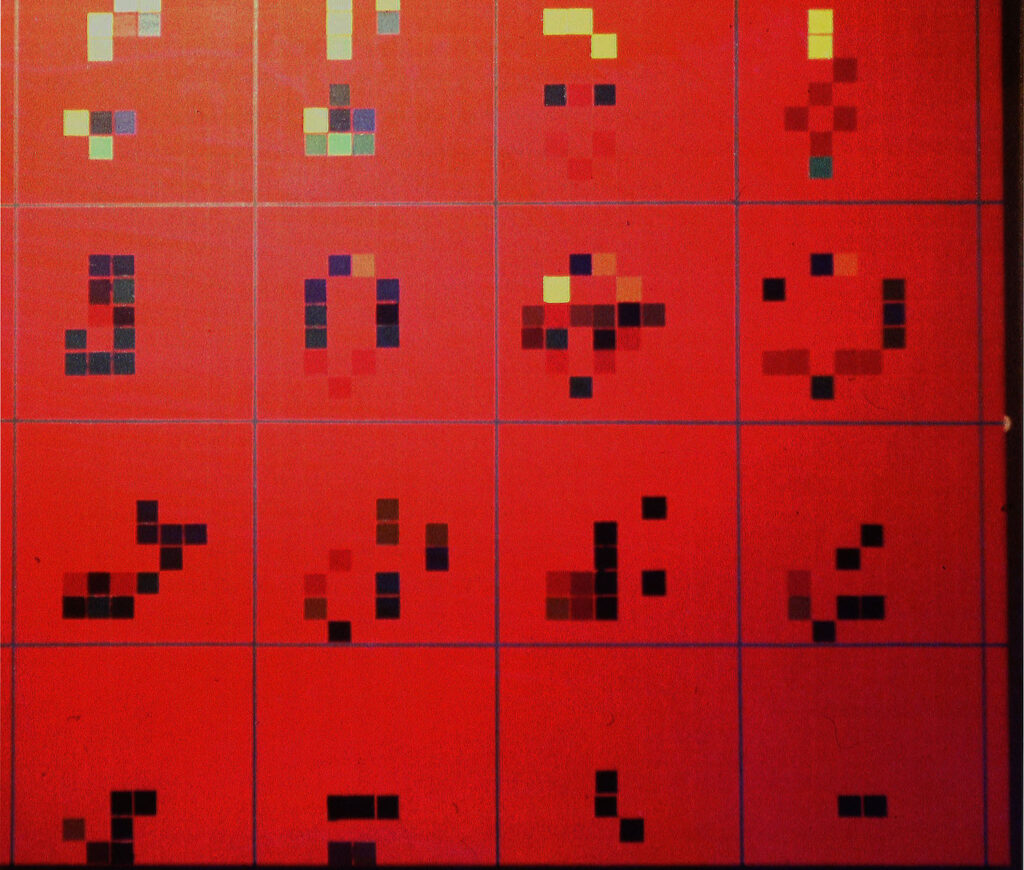

Over fifty years. My studies at Derby College of Art in the early 1960s were transformative. I found Keith Richardson-Jones to be an inspirational tutor. The basic design course he taught was a model of its kind, associated with the radical teaching of Victor Pasmore & Richard Hamilton at Newcastle, Harry Thubron in Leeds, and Tom Hudson in Leicester, and having its roots in the curriculum of Johannes Itten at the Bauhaus. At Derby I appreciated its structural logic, range of technical disciplines and rigour in the development of critical evaluation of visual subtleties. The interplay between figuration and abstraction was significant. I came to recognise that there were important aspects of art that this education, which was essentially formalist, neglected but I was fortunate to be in the midst of lively arguments between KR-J and an ‘old guard’ of tutors steeped in the traditions of the academy. I was part of a small group of very committed students each one of whom brought ideas and challenges to the course. Seeing the 1961 exhibition of paintings by Mark Rothko at the Whitechapel Gallery was revelatory and inspiring. I also benefitted from a taught course in philosophy, ‘complementary studies’ that included lectures by visitors engaged in a very wide range of occupations (actors, musicians, sound poets, an undertaker, an aeronautical engineer) and many ex-curricular experiences including cutting-edge modern jazz and modern experimental music including John Cage. It was the era of wonderful new music by the MJQ, Dave Brubeck, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman. We took part in open exhibitions and organised others. After a year’s teacher training in Manchester I started teaching in Derby and began painting independently and very energetically. I remained closely associated with the College of Art, was actively involved in the ambitious Derby Group and was soon invited to become a member of The Midland Group, Nottingham, exhibiting extensively in the UK. My first solo exhibition was at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham (1966) and was well reviewed. Paul Klee’s notebooks The Thinking Eye, Sir D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form and C.H. Waddington’s Behind Appearance were significant books in establishing that my approach would involve research into the development of forms and be experimental in character. The biomorphism of my work in the 1960s gave way to a series of paintings arising from my engagement with The Life Game of the mathematician John Horton Conway. This was informed by systems painting, the innovative minimalist works of Steve Reich and the poetry of Robert Lax. This interest in the structure of things as the product of processes is an enduring interest and eventually found its focus in my ongoing work which is underpinned by studies of mining and quarrying.

With such a rich and long-lasting practice, there are so many questions one could ask about your work. Equally rich are two concepts that inform your work: landscape and labour. Could you tell us a bit more about those concerns.

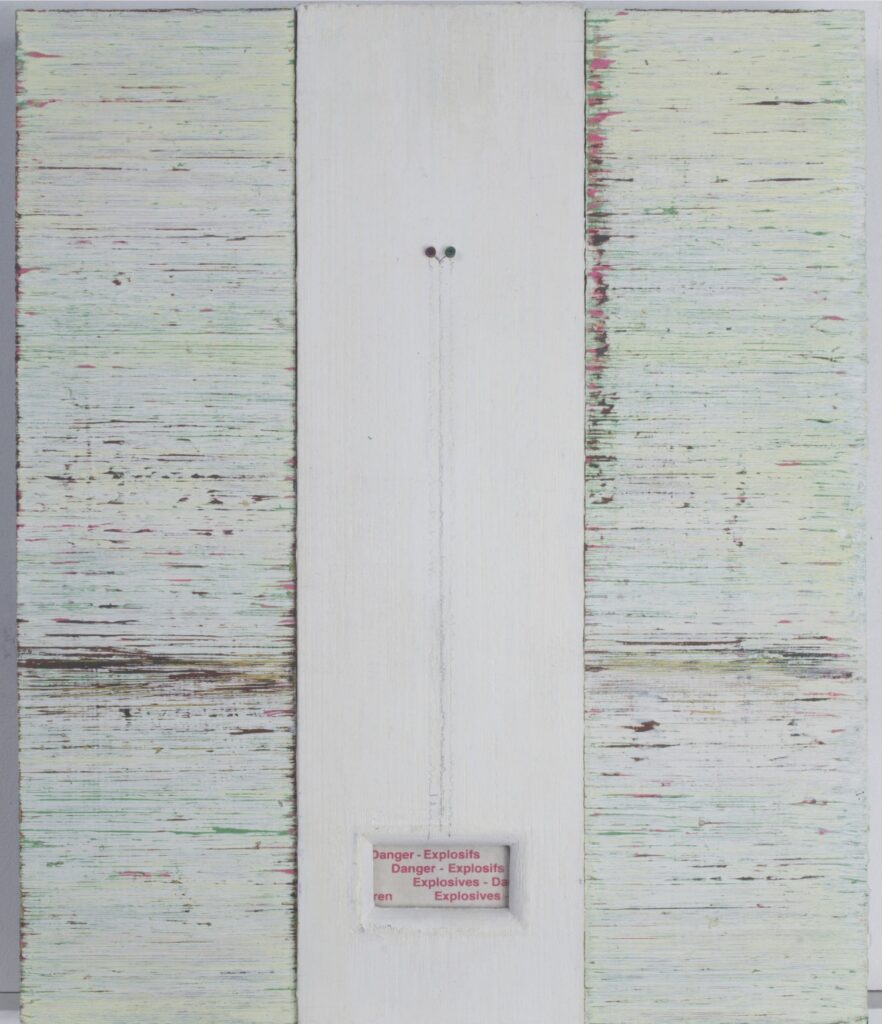

I recollect standing on the Gang Vein, on the White Peak limestone plateau, just a short walk from my home and viewing the 360° panorama. To the east there is the dark gritstone outcrop, Black Rocks. To the north Masson Hill and the Heights of Abraham and High Tor in Matlock Dale, a landscape depicted by many artists including Joseph Wright, Alexander and John Robert Cozens, and Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg. It is natural to lift one’s eyes to this spectacular scenery. When first I knew this place few of the numerous lead mine shafts were capped and an unwary walker risked a sudden and dangerous fall. Keeping my eye on the ground led me to revise my view of landscape and to investigate what lay below. I later understood that my experience of dropping a stone down the shaft of a lead mine corresponded to an epiphanic experience of W.H. Auden in the North Pennines when, in his poem New Year Letter “The reservoir of darkness stirred.” Coincidentally I photographed Dale Quarry (‘The Big Hole’) in Wirksworth, fascinated by the negative/positive relationship between the huge empty space and the buildings that sat around its top edge. My interest in these places lay in the labour undertaken by miners and quarry workers and the fact that, in the tradition of landscape painting, this is largely unrepresented particularly in contemporary art. Peter Lanyon’s work on the tin mines of Cornwall (especially St Just, 1953) struck me as exceptional in addressing this subject in a manner that embodied experience and history through an innovative approach to painting. In my Quarrying Series I deliberately challenged the conventional landscape format, making tall very narrow paintings that invited scanning down rather than across. When researching mines I became engrossed by learning that, before explosives, miners progressed along a vein by cutting into hard rock with small picks at the rate of about a handspan a day. Their efforts are evident in grooves inscribed in the sides of levels. In some places these small repetitive marks are known as ‘woodpecker work’. Edward Casey in considering the etymology of the word ‘landscape’ draws attention to its possible roots of ‘scape’ that associate it with ‘scrape’ and ‘scoop’. I am engaged by the fact that landscape is as much what is cut out as what it built up. The success of great landscape paintings of the past, and the aesthetic pleasure they give, has blinded many viewers to human endeavour that has shaped our surroundings. In contrast to painting photographers such as Edward Burtynsky, Sebastião Salgado and Emmet Gowin have made wonderful work that relates to this aspect of landscape. I have found more significance in the work of so-called ‘land artists’ such as Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Michelle Stuart, and Richard Long than I have in most contemporary landscape painting which too often manifests clichés of scenery and atmosphere (sometimes abstracted). Amongst few notable exceptions I would cite Prunella Clough whose commitment to representing aspects of industrial landscapes at a time when they were widely overlooked in painting was distinctive, always subtle and imaginative.

The impact of physical endeavour and scarred places are made beautiful in your work. Is it your intention to elevate these scenes from an industrial context, to make them beautiful, to present an alternative picturesque?

I’m pleased when my work is found beautiful. There may seem a paradox in associating places that are scarred by quarrying and mining with beauty. I’m not sure about ‘an alternative picturesque’ though. I recollect Francis Bacon speaking of ‘the beauty of a wound’ which made me uneasy in that I couldn’t imagine distancing myself so much from the injury inflicted to view it objectively but perhaps that is akin to the professional distance that a surgeon must maintain. I gain aesthetic pleasure from some industrial landscapes but always for me there is the recognition of labour. The extractive industries, whilst often regrettably involving environmental despoliation and exploitation of people, demand skill, courage, perseverance, tacit and explicit knowledge, and a feeling for natural materials. There is beauty in work well done. Richard Sennett in ‘The Craftsman’, quoting a treatise from 1540, wrote of how the origins of modern mining technology lay in the understanding the surgical dissection of Vesalius, illustrating how the stripping back of strata in layers was more efficient than simply chopping through earth. The mining of precious rare earth elements today as portrayed in Steve McQueen’s film Gravesend is a reminder of often overlooked human labour involved in meeting the demands of technology on which modern society has come to rely. I like the word ‘elevate’ in your question. Miners sometimes have used the phrase ‘brought to grass’ when speaking of ore brought from underground to the surface. I hope that in my work I capture people’s attention to a degree that they spend time looking beyond the surface to the point at which ideas, feelings and associations are elevated and potentially revelatory, enriching perceptions of landscape and landscape painting.

Is it your desire for the viewer to be conscious of the meticulous, concentrated processes that you employ – layering up and paring down – to produce such clean, subtle works?

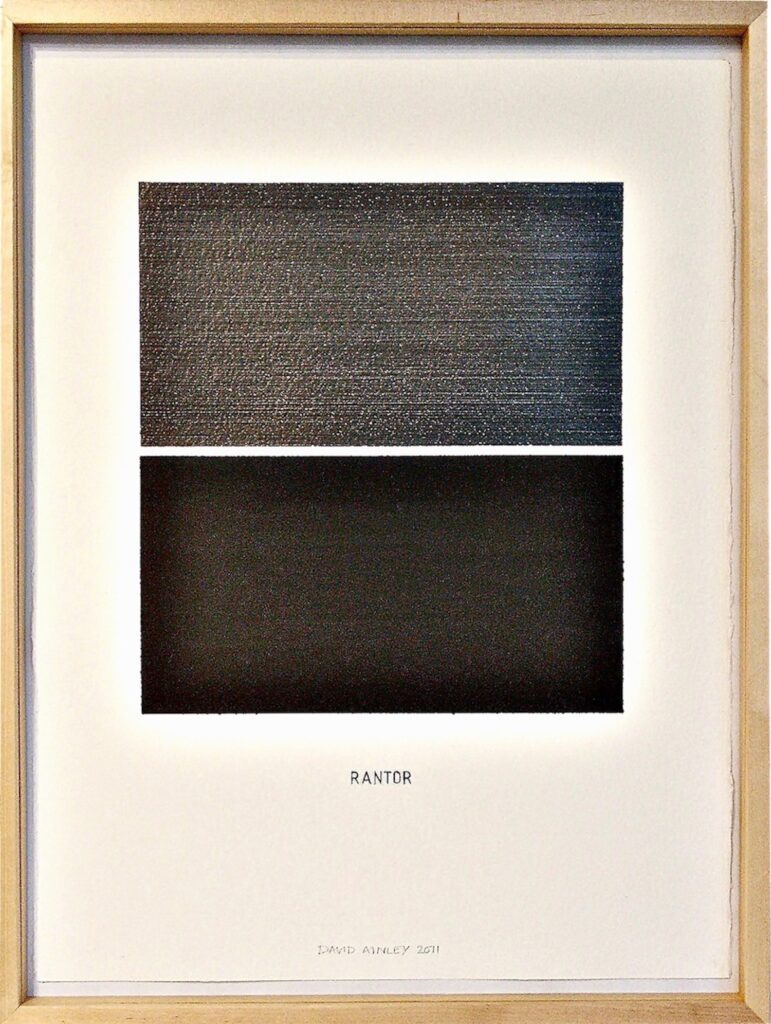

Yes, but not limited to an insight into technique. It might not be the first thing a viewer is aware of but, when they are drawn into the work, close attention will reveal something of its making that is integral to its content and concept. When viewed at first-hand the physicality of most paintings will often come as a surprise to viewers who have only ever seen works as digital images. People who are aware of the ‘object-quality’ of painting will often notice the edges of a canvas looking for evidence of the layering of colours. In most of my paintings formal elements are sawn through the support. I draw with a saw. Lines that are derived from the location of mineral veins are produced in this way. The cross which features in each of the ongoing series Landscape Issues is cut out and, before reinserting, is sometimes reorientated or even moved from one painting to another. Mostly I paint only in monochrome layers, each one of which has numerous lines individually drawn through it with a hand-held blade before that surface is scraped down and totally overpainted with another colour before re-drawing with lines and re-painted. And so on, layer upon layer until the painting has an object-quality that embodies my feelings for the subject. In paintings that are resolved (or, echoing W. H. Auden’s remark about poems, following Paul Valéry, abandoned) the subtle surface that is produced holds myriad flecks of colour each one indicative of a layer of underlying monochrome. Sometimes these create optical mixtures but much less determined than in the pointillism of George Seurat.

What is important to you in maintaining and motivating your practice?

To remain intellectually and creatively engaged and challenged by my work and that it should become known and enjoyed more widely by anyone interested in the study of landscape, labour and critical practice in painting.

What have been your biggest achievements since establishing your practice?

By most measures my achievements have been modest. Sustaining a focussed practice for nearly six decades throughout most of which I was also able to teach creatively and continuing to feel that there is much still to be done and discovered is, I guess, an achievement. I am pleased to have been selected for the Jerwood Drawing Prize on three occasions (once having all three of my drawings shown) and it has been satisfying to have had my work exhibited here and, especially in the last few years, in museum shows abroad. I have been particularly pleased that my work is associated with a 5 CD box set of Morton Feldman’s music for solo piano played by Philip Thomas and released by Another Timbre through which it has reached a large international audience.

What have been the biggest challenges to your practice?

Managing time for research, studio practice, writing and reflection amongst all the other quotidian demands of a normal life, university teaching, and various administrative details and communications concerned with art has been challenging.

What is the most interesting or inspiring thing you have seen or been to recently, and why?

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic I have been in lockdown so have made no excursions recently. The view I have of landscape is a constant stimulus. I am nourished by listening to recorded music and discussions of music on Radio 3 and by radio broadcasts on any aspects of creativity, in art, in science in business etc. The last great show I saw was of David Smith’s sculpture at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Which other artists’ work do you admire, and why?

I admire Cézanne for his persistence and his heroic struggle to resolve the relationship between the eye and the brain in beautiful paintings; Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation of Christ for its poise and complexity; the passionate rationalism of Nicholas Poussin whose Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, is a favourite painting of mine; the Suprematist works of Kasimir Malevich; Mondrian’s Compositions; Sol LeWitt’s questioning of the authorial hand; Ad Reinhardt’s Black Paintings are simply beautiful and a challenge to all painters; Carl Andre’s sculptures; On Kawara’s Date Paintings, though ostensibly simple and repetitive, are individually quite particular, beautifully crafted, and deal with big ideas; Giorgio Morandi’s still life paintings are about so much more than jugs and vases; Agnes Martin and Robert Ryman focus attention on how so much of beauty can be achieved when working within self-imposed restraints; the labour intensive sculptures of Martin Puryear; Brice Marden and Callum Innes have unwaveringly had a commitment to making beautiful paintings throughout a period when there have been interminable arguments about the value of the medium, abstraction and figuration. Philip Guston’s moral courage and independence resulting in his unsettling later paintings has my great respect. I could extend this list. I should mention some landscape painters: Constable, Turner, Paul Nash, Peter Lanyon, Prunella Clough, Carol Rhodes and land artists including Robert Smithson. Beyond those I have identified I value the company of many artists past and present including, of course, my wife Joan Ainley. I am fortunate to have many artist friends, some of whom are members of Contemporary British Painting, whose work I admire.

Where do you see your work in the next 5 years?

When one is older the years pass unnervingly speedily. I should perhaps think along the lines of Katsushika Hokusai who said “When I am 80 you will see real progress. At 90 I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At 100, I shall be a marvellous artist. At 110, everything I create, a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before.” Hokusai lived to be 88, leaving a body of wonderful work. I have a great deal to do by way of organizing many years’ work and an archive. It would be good to think that I might be able to show my work in some substantial exhibitions, that there will be new pieces and that I find opportunities for writing.

Who would you most like to have visit your studio?

I would love to be able to discuss my interests in art and place with Lucy R. Lippard. Her scintillating writing has accompanied me through most of my career, from Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (1973), Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory (1983) and Undermining: A Wild Ride through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West (2014).

Where can we see your work? Do you have any upcoming exhibitions, events or projects?

I show in the UK and abroad in exhibitions organised by Contemporary British Painting. Solo exhibitions happen every few years and my work is sometimes selected for national open shows and other curated exhibitions in the region and beyond. Occasionally I give public lectures. The present period of Covid-19 lockdown has meant that future plans are on hold.

David was interviewed in June 2020.

All images are by and courtesy of the artist.