Michael Sanders is a sculptor and photographer working from a former military airfield in Lincolnshire. His practice often subverts the everyday: as the blundering nuclear tourist he makes gentle interventions at former Cold War and nuclear sites, using tartan and textiles to challenge and re-appropriate the imagery and symbolism of military power and technology.

Where are you based?

I am based in quite an isolated place in rural Lincolnshire. I work on a trading estate near Louth. It is on the edge of an old military airfield. There are plenty of comings and goings and it can occasionally feel a little like cowboy country. My workspace is more of a metalworking workshop than a studio. I have a darkroom there; it’s good to have somewhere clean to retreat to. Something completely different from metalwork and welding.

Describe your practice for us?

The core of my practice is sculpture and photography, although it increasingly includes an element of performance in the form of ‘gentle interventions’. I see a common thread running through my work. Much of it is about people and places touched by conflict. Even in my most recent project Us, A Gunby Estate Domesday, about the tenants on a National Trust estate, little hints of past conflicts crept in.

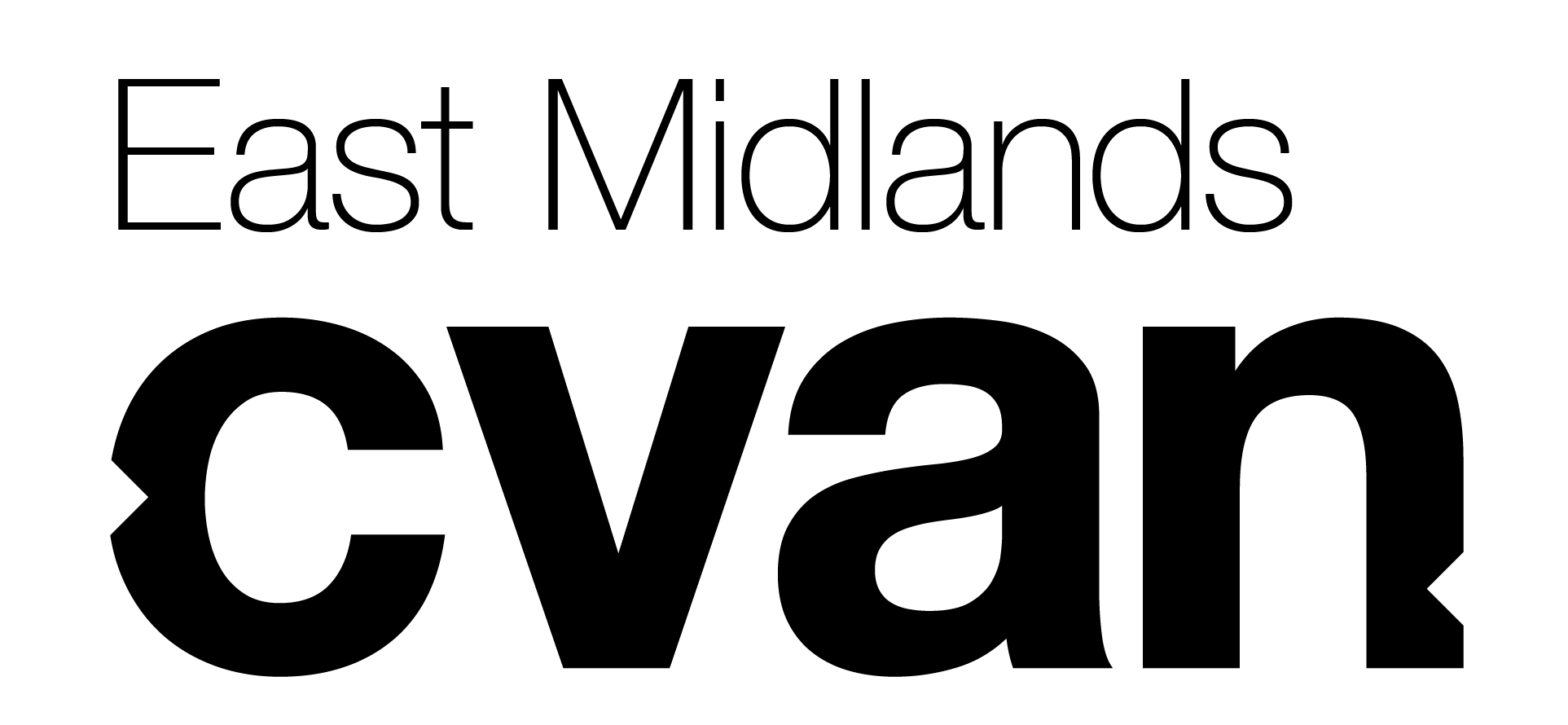

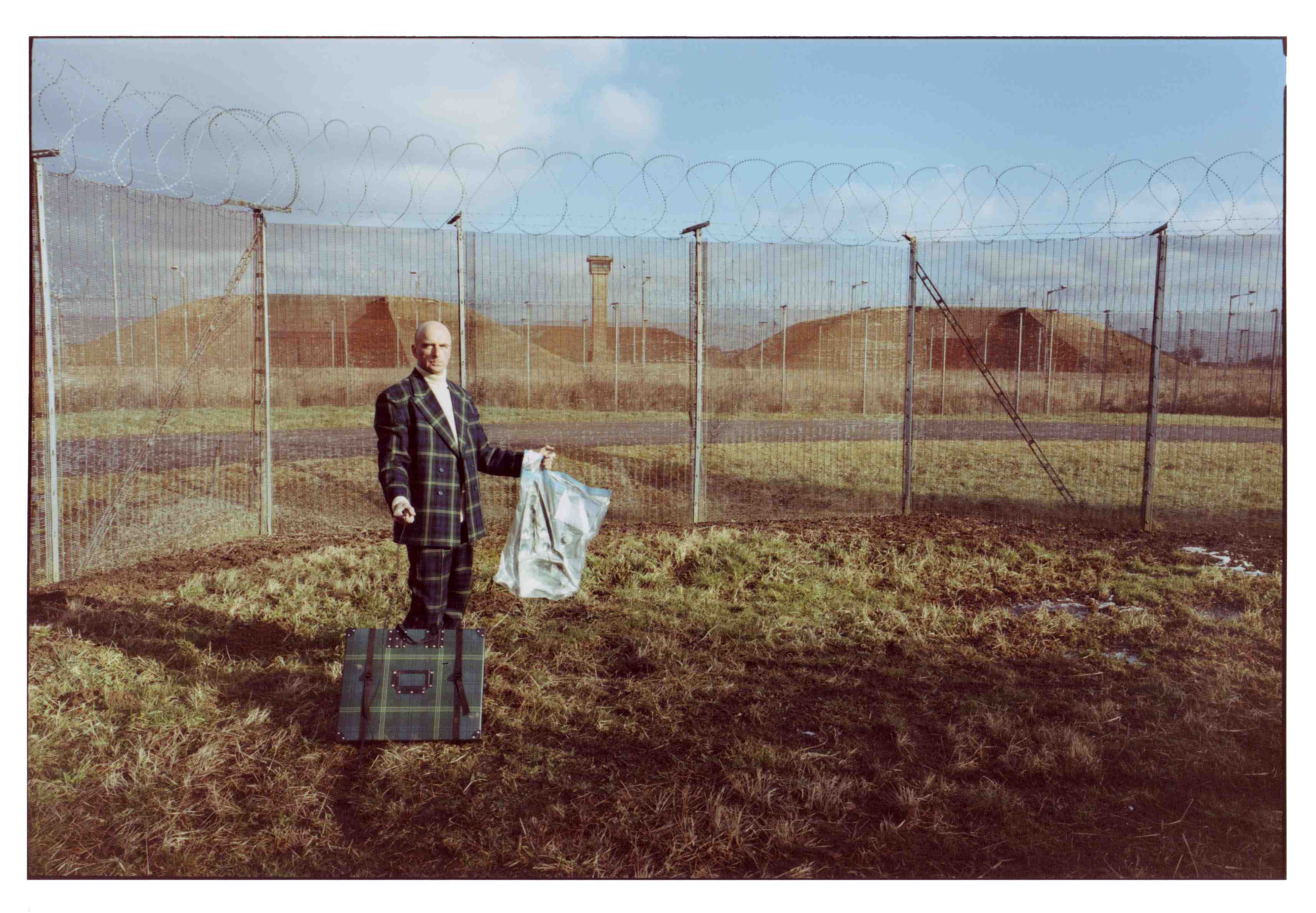

My work involves quite a lot of self-portraiture. This is in part because of budget as well as not always being able to get anyone to come out and play. It also means I can travel light and not draw too much attention to myself when working. (See RAF Molesworth 30th Anniversary and tartan suit)

Like many artists, I don’t like to be pigeon holed. I aim to use the most suitable techniques and materials to explore and express my ideas. I feel my work is quite concept driven but I have some difficulty conveying my ideas in the written form. I prefer to ‘think with my hands’. I certainly feel more productive when I am making something.

When I adopt the persona of the Blundering Nuclear Tourist, I wear a suit in a tartan called Polaris Military. Officers and men of the US Navy originally commissioned this tartan when their Polaris submarines were stationed at Holy Loch in Scotland in the early 1960s. It was the first tartan to be registered for a ship or nuclear weapons system. I wear the suit when visiting cold war and nuclear sites around the world, in part to try to reverse or return the original cultural insensitivity of the tartan.

The tartan has appeared in other works like COLDWARmHOTLINE. The telephone box was shown in London just before the 2012 Olympics as part of the BT ArtBox project, It was intended as a nuclear Rossetta Stone. The tartan is made up of lists of nuclear places and weapons systems, a sort of cold war memorial. A completely unintended consequence of viewers photographing this work might be that they are breaching the Terrorism Act 2000, where it is an offence to collect or possess “information of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism”. (See COLDWARmHOTLINE Tartan Telephone box close up and COLDWARmHOTLINE Telephone Box and tourists outside MoD)

How long have you been practising and by what route did you come to your practice?

I have been practising since the mid 1980s. I studied 3D design at Manchester Polytechnic. After this I worked for a while as a Fine Art technician at Middlesex Polytechnic. While there I attended various short courses, one a welding course at British Shipbuilder Training Yard on the Tyne. Welding became a big part of my practice and how I have made my living over the years.

Of your work you refer to ‘investigations into future archaeology’, can you expand on that notion?

It comes from the title of a joint show with Walter Cotten in 2008 at the Kruglak Gallery in California. Ruin – Investigations into Future Archaeology. Walter had previously photographed a high level nuclear waste dump – the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in Carlsbad New Mexico for the Centre for Land Use Interpretation and we had discovered the proposed scheme to prevent people accessing the site for the next 10,000 years. These sites clearly defy archaeology. In a previous show Trinity at the Horse Hospital in 2005 we speculated on the need to deter inadvertent human intrusion at these sites, making our own futile marking schemes and playing with the language and signage that might be needed for a future period beyond our civilization’s own experience of known or recorded human language.

For the Ruin exhibition I included work about the accidental damage to the archaeology at Babylon after the second Gulf War when an allied military camp was built there and amongst other things sandbags were filled by digging into the archaeology. I wondered how we might protect our high level nuclear waste sites far into the future, if we failed to protect a known heritage site now.

Future archaeology is also my way of seeing and imagining how archaeologists of the future will interpret our world. What will they make of all the vast concrete structures and bunkers designed to survive nuclear war or the Stanford military training area in Norfolk, which contains villages evacuated in the 1940s that have since been used for urban warfare training? Through time they have become East German villages, bits of Northern Ireland and most recently an Afghan Village. Surely this will confuse any future explorations.

You’ve experience in the field of engineering, does that inform your work?

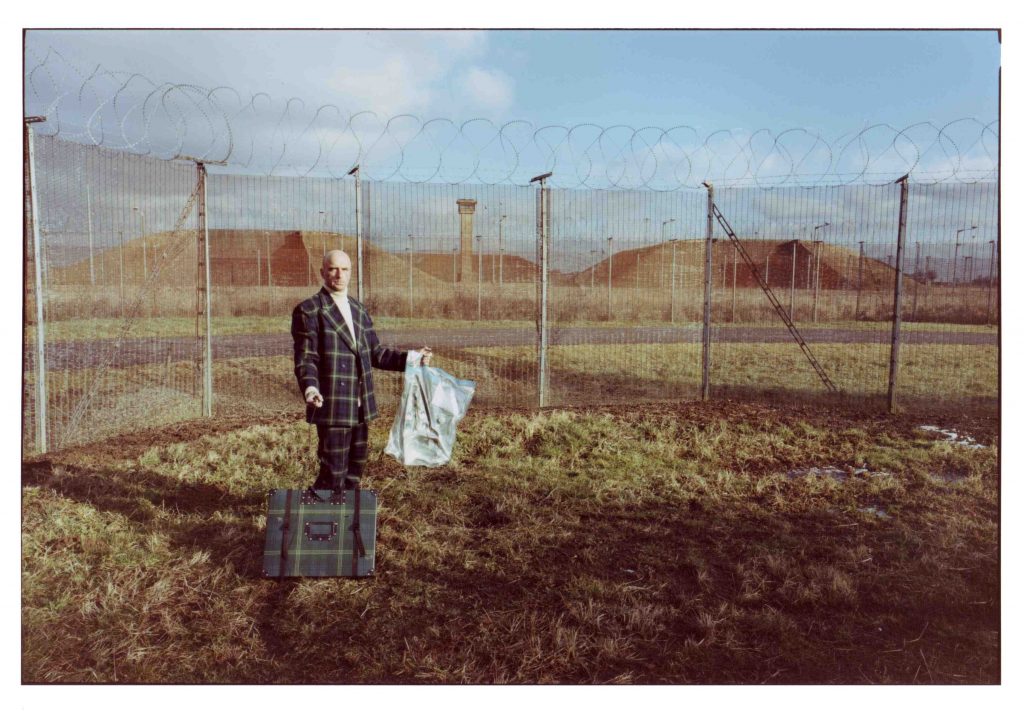

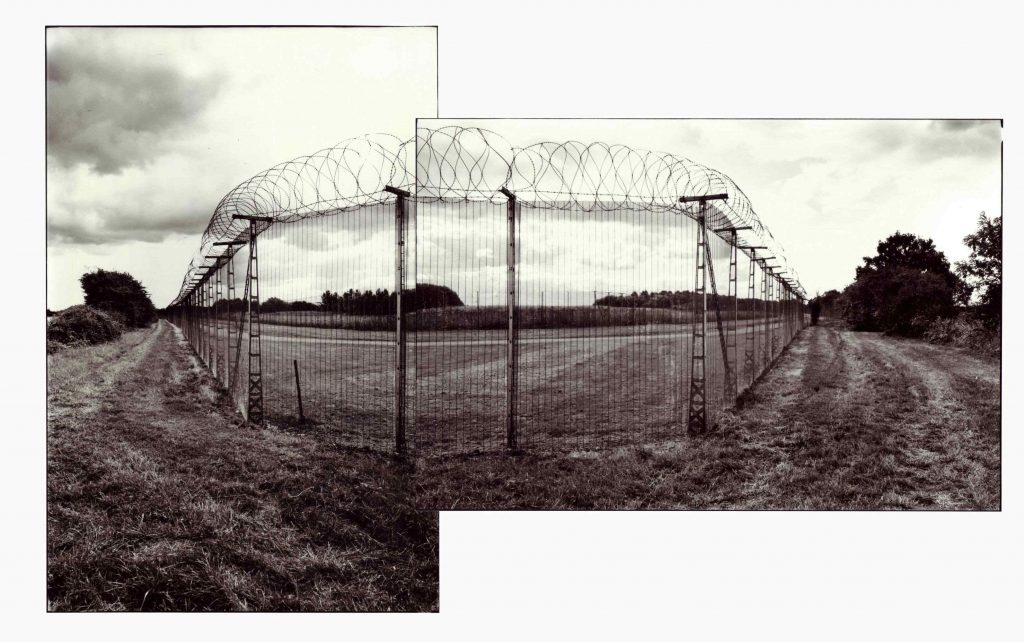

Yes, I would say it was a fundamental part of my work. I am exploring my own love-hate relationship with military technology and trying to expose what I perceive as good and bad uses of technology. When I first came across Razor wire, it was being used to encircle RAF Molesworth in 1985 (prior to construction of a cruise missile site), I couldn’t believe someone had actually sat and designed this material. This led to my making the chair ‘Sitting Comfortably 1987’. (See Sitting Comfortably, 1987, Razor wire chair and Fence and Bridleway RAF Molesworth, 2013)

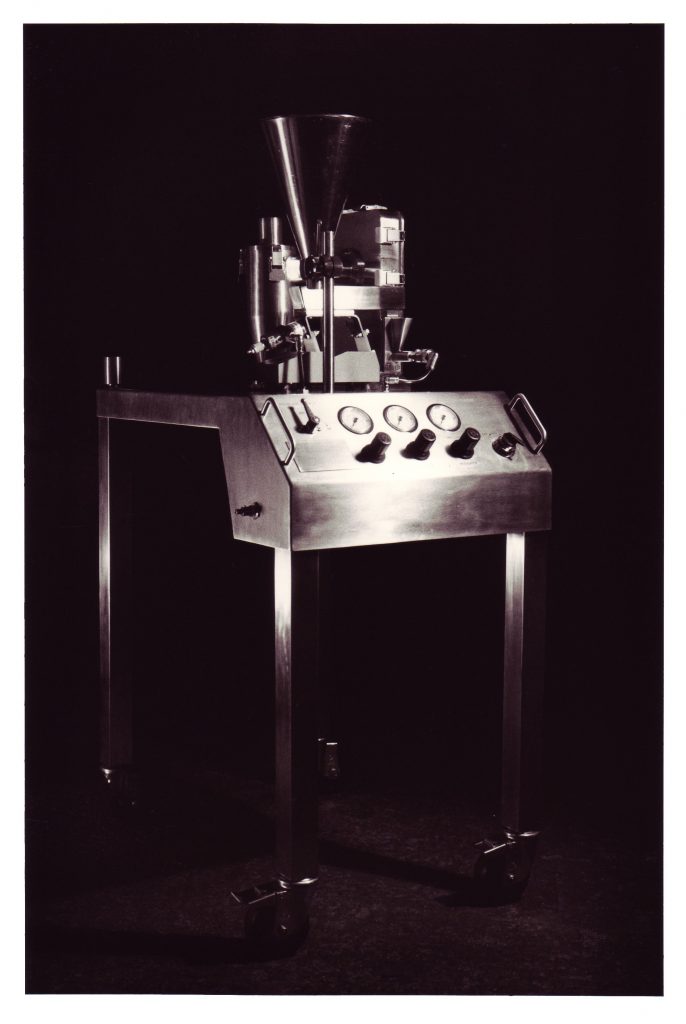

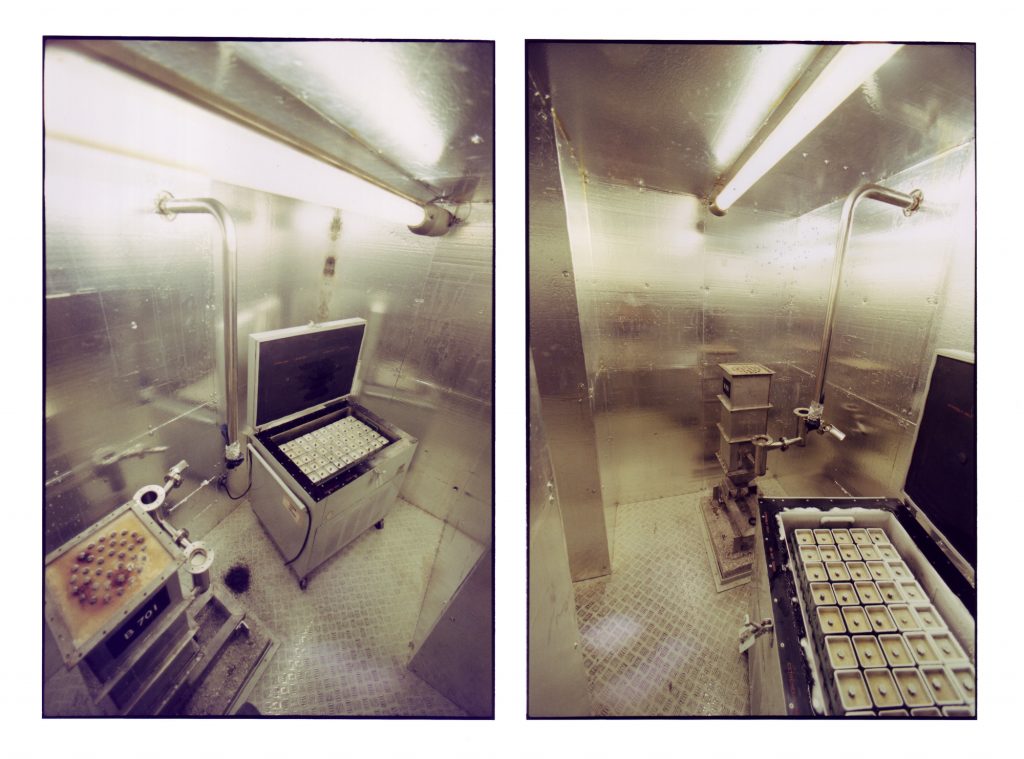

I inadvertently made a pharmaceutical machine for British Nuclear Fuels Ltd in the mid 1990s. The arguments over whether we should be doing this kind of work caused tensions in the engineering business where I was subcontracting. I was told the machine was not for nuclear use but was to create an experimental powder to feed to rats so that they could breathe underwater for up to 30 minutes. (See Equipment).

I retained the blue prints and later remade parts of the machine in an installation called ‘shine paths’ loosely based on building B701 at Sellafield, a building where 10 000 litres of radioactive liquor were said to have leaked (unnoticed) from a holding tank into the surrounding ground. Workers passing the building were said not to linger because of the ‘shine paths’ emanating from the building.

The installation exhibited at Shoreditch was my imagined artistic response to something which concerned and confused me and about which I had felt powerless. (See Shine paths installation_1997)

Some of your work has a connection with military practices and you sometimes put yourself in these works through performance, is this at personal risk? Does this make it hard to work with organisations who might be nervous of such interventions?

No, there is little risk and I do not want to overdramatize this (nor do I wish to appear cavalier). There have been times I have been worried or even fearful when taking pictures in our land. There can be tension, uncertainty and misunderstanding; this is a little frustrating and maybe revealing.

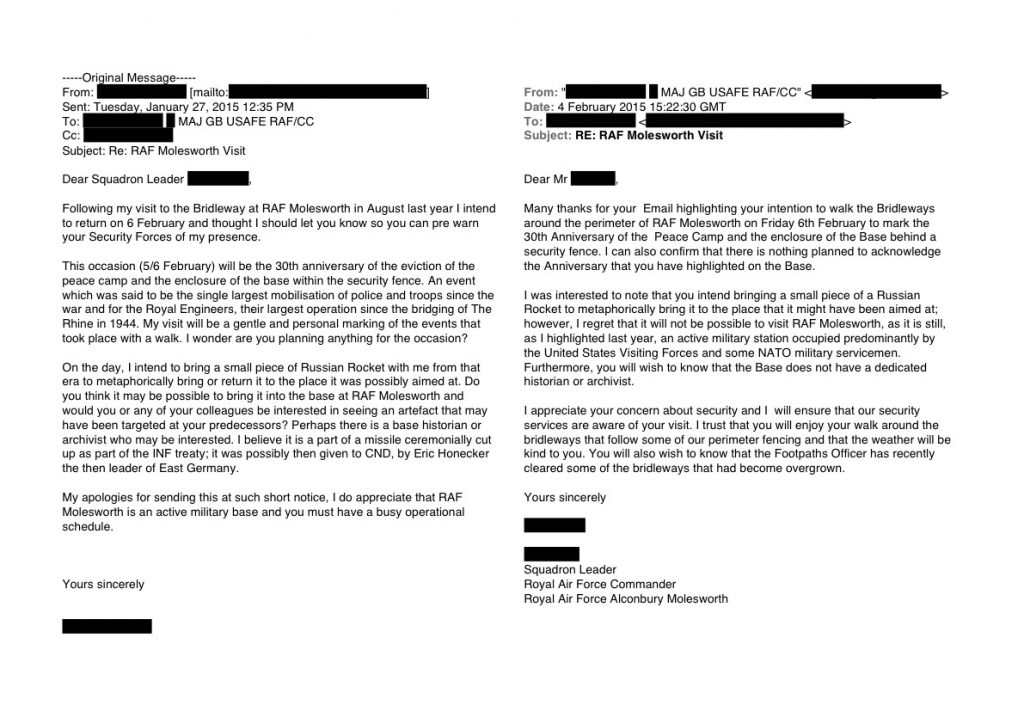

Certainly In the current security climate, I would hate to waste any one’s time or cause an unnecessary alert. So I try to make arrangements by prior negotiation. I see these negotiations as part of my practice. (See RAF Molesworth Correspondence (redacted). If you look at the self-portraits I try to look defiant but I think they also show a vulnerability set against something bigger than myself.

In truth, I would prefer to work in collaboration with the military to shed light on their activities but because they perceive my work as critical, it can be hard to do so as they often see little benefit for their cause. I don’t feel this to be so, one of my most successful works was the radio programme Target Practice for Radio 4 made in collaboration with Katie Burningham and set at RAF Holbeach. It took some relationship building but in the end I felt we told a fascinating story in a fair and balanced way.

https://soundcloud.com/fallingtreeproductions/target-practice

I suppose one risk of this work is that of developing ‘Stockholm Syndrome’, where one falls in with the cause of one’s captors.

What is the most interesting or inspiring thing you have seen or been to recently, and why?

Richard Mosse – Incoming at the Curve Gallery in the Barbican. Simply the best show I have seen in years. It was so powerful and engrossing. A perfect mix of visuals and sound and a work that I wish I had or could have made.

Which other artists’ work do you admire, and why?

Trevor Paglen, His work – Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground

Dugway, UT which was photographed 42 miles from the subject with a home made camera. It shows me there are always new and creative ways of approaching a subject.

Fay Godwin – Our Forbidden Land was a great influence on me.

Grayson Perry – He is such a clear and eloquent advocate for art and is such a good people person

Viv Albertine – for her wonderful and revealing autobiography, which captures the ethos of the early punk movement.

Robert Wilson. The work Walking 2012 at Norfolk and Norwich Festival appeared so simple but was like a swan gliding along, the legs paddling away furiously underneath.

Where can people see your work?

On my websites: one is quite out of date and has old work on it, a new site is being developed, as well as on the Heslam Trust website.

Michael was interviewed in December 2017.

All photographs are courtesy of and taken by the artist except where stated.