Meet the Artist started in 2014 as a way to recognise and platform the incredibly ambitious work being made by artists based across the East Midlands! Following an extended break Meet the Artist is back for a limited run, which will see CVAN EM platform work by an artist from each county in the region.

Fiona Carruthers is a visual artist working across installation, performance, sculpture and photography. She was awarded an MA in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins in 2022 with distinction, a Final Project Award and Central Saint Martin’s Tension Gallery Prize.

Recent residencies include an AA2A Residency at Loughborough University (2022/23) and a Sustainability and Environment Residency at Lincoln Museum and Usher Gallery (2021). Selected group exhibitions include Artists in the Now, a UK New Artists/MashUp showcase of up-and-coming contemporary visual artists from Lincolnshire (2023),Points of Return at The Umbrella Arts Center in Concord, Massachusetts (2023), and Merch, at the Lethaby Gallery, Kings Cross, London (2022). Recent solo exhibitions include, Below the Radar at the North Sea Observatory (2022). Carruthers’ work is held in private collections.

Where do you practice?

I recently joined CORESET, a newly formed creative studio in Newark, and am developing my practice there after a few years of working without physical space. I feel very fortunate to be part of a supportive and vibrant community of creatives. We are committed to connecting and sharing: united in our ambition to find new ways to speak to audiences and generate meaningful societal change. We want the space to be extraordinary: a fertile ground for collaboration.

How does your locality shape your work?

My sense of self as well as my creative motivation and ambition, are profoundly affected by my experience of growing up and living in the remote countryside and coastal areas of Lincolnshire. Forty Percent of Lincolnshire’s land is at or below sea level and the consequences of the changing climate on the well-being of human and nonhuman ecologies across the region, are easy to see. Uncertainty here is palpable: personal and ever-present.

My physical disability and post-traumatic growth, both outcomes of having survived local flooding, have furthered my understanding of what it means to be human and how inextricably linked we are to nature, other humans, other species, and the land and sea. From my exposed position of survivor, it seems obvious that the world is not things, but processes: transformation, shape-shifting, slowly morphing habits and mutuality.

The process of survival, I realise, is an unsought, unspoken and powerful imperative that drives all forms of life.

What do you practice?

I want to better understand what it means to be human, and posthuman, and am preoccupied with speculating about the future of our species and environment. Sustainability and survival and the need for social and emotional transformation sit at the heart of my practice. I wonder what it will take for humans and nonhumans to co-exist.

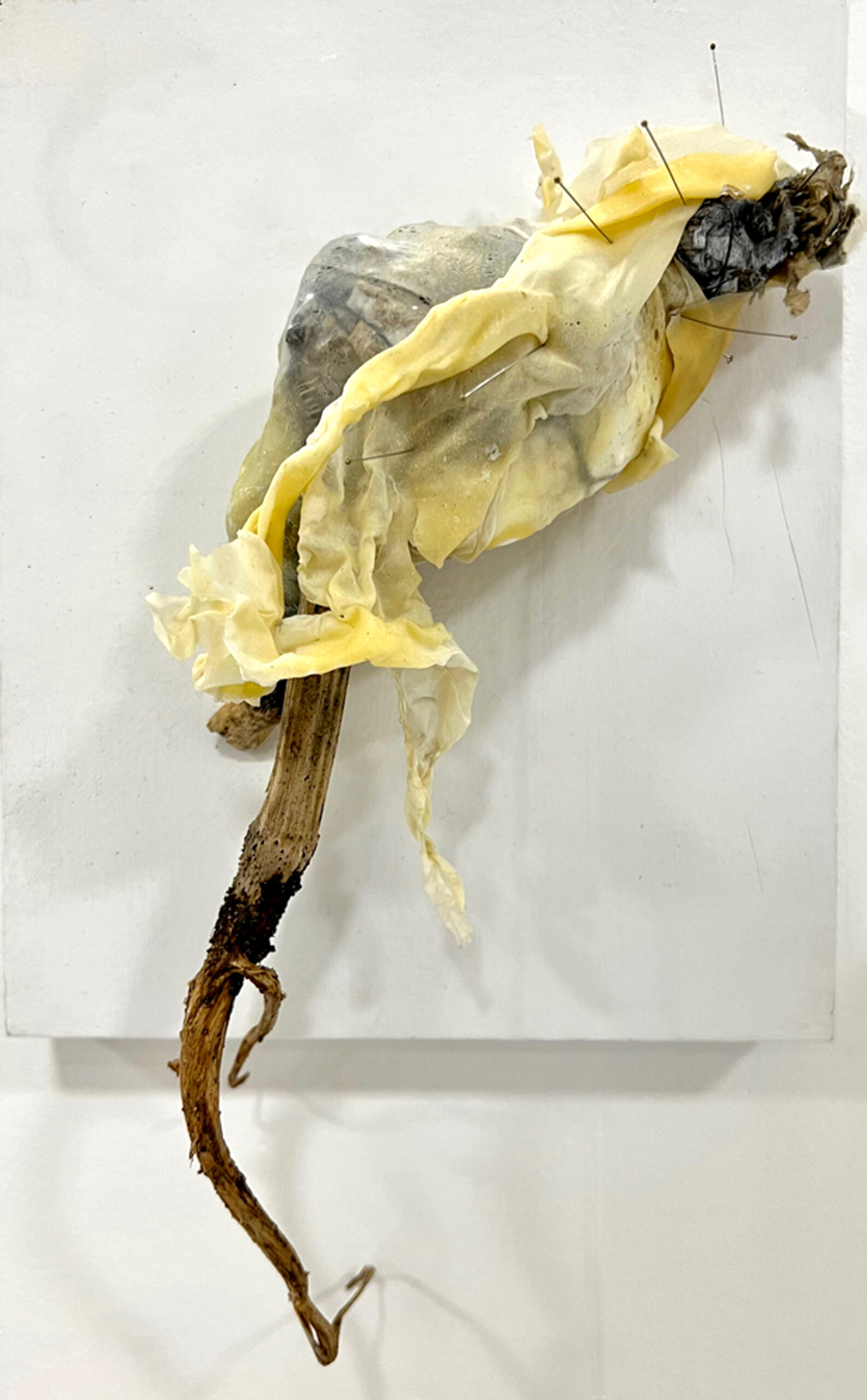

Typically, my search for understanding manifests as transience, fragility, precarity and uncertainty. On-the-point-of-collapse installations, performance and constructions using found and recycled materials, everyday ephemera, elements of nature and the in-between sites in our surroundings that are unseen and overlooked. The significance of these is their wider invisibility, lack of perceived value, and potential to point to the need for political and social change.

Installations and constructions are assembled so that each component, including viewers’ behaviour, has a role to play in the work’s existence. In their new and unexpected roles and responsibilities, their differences are revealed, yet together they are united in a shared future. This is a new community, emerging from human and nonhuman. In my work and practice, I am looking for cooperation: mutuality and inclusivity. I am proposing this as a practical tactic for survival and a proposition for a better, not-quite-familiar future.

A commitment to the ongoing care of on-the-point-of-collapse structures is intrinsic to my work. This can be seen as an expression of our best human nature, vital to our collective flourishing. This can also involve the laborious, repetitive and futile actions of monitoring, maintenance and rebuilding. I often wonder if I am performing this role as a strategy for managing my anxiety about the future.

My work is an invitation to the viewer to slow down: to linger, engage with all their senses and become more spatially and socially aware of themselves and their surroundings. I want to stretch out a small story of now and create space to pay attention to our human nature and humanity’s relationship with the world.

Sensing is a process, and a somatic connection between my work and its viewer remains crucial to my desire to (re)connect human physiology with the environment.

What are you working on?

I am using my studio space to explore, examine and study. It is a luxury to be able to pay attention to the rhythm of objects and mark-making in space and to the unintentional patterns and relationships that emerge from these. The ongoing need to stimulate the perceptual and physical sense of precariousness and heighten the process of sensing seems inevitable. Although very early in the process, aspects of this work have become more explicitly sculptural.

Mutuality, as a generative and practical proposition for survival, remains central to my thinking and making while the existential push and pull at the water’s edge is being explored for its potential to reveal the sublime in the fragility and vulnerability of our nature.

The NoLand that exists between land and sea too, offers a plausible metaphor for the state of limbo in which we find ourselves in today’s uncertain political and ecological moment. This presents itself as an other-worldly space in which new forms of multi-species can be imagined: the more-than-human and the as-yet-unknown mutations responding to changing environmental stresses.

I hope to discover the no-longer and the not-yet, a record of what we are ceasing to be and the seeds of what we are in the process of becoming.

How do you engage audiences with your practice and the themes that shape your work?

Engaging audiences with my practice and themes is influenced by the understanding that paying attention to and with our senses is how we make sense of the world. This is a prerequisite to meaning-making, understanding and imagining.

The strategies I use in my work to engage others include interrupting and manipulating viewers’ movements and drawing them into an active physical and complicit situation. The viewer is quickly comprised and obliged to pay closer attention to themselves, others and their surroundings.

I also aim to engage viewers by triggering their curiosity and anticipation, both powerful feelings and behaviours key tosurvival. On-the-point-of-collapse structures communicate a sense of unease, precarity and uncertainty and the not-quite-familiar landscapes, sites, and events emerging from these are often described as enigmatic. The spectacle of light, sound and movement is used to enhance these effects.

Materials and objects are selected and assembled in part to generate intrigue and even surprise. They are chosen for their everyday familiarity: their ability to evoke associations and memories and are situated to help tell the story as well as embody it. A well-delivered story prompts a rush of hormonal changes in our bodies which helps prepare us to pay attention, motivate us to work with others and take positive action.

A range of formal and informal engagement activities involving sharing motivations, processes and outcomes, digitally, verbally and in printed formats, helps to engage diverse audiences. Within each opportunity, I am looking for the potential to affect and to be affected. The political theorist Massumi states that to affect and to be affected, is to be open to the world and change. And, it is this conceivable change, he argues, that makes effect immediately political.[1]

How do your considerations around environmental sustainability connect with sustaining a practice as an artist?

Weaving information and ideas into my work from across humanities, science and art fuels my practice. I am looking for insights and a more sophisticated appreciation of the complexity of today’s environmental concerns. This ongoing process folds into and feeds my creative decision-making: informing lines of inquiry and helping direct my study, experiments and tests.

Environmental sustainability relies increasingly on a commitment to cooperation and exchange: sharing knowledge, fostering new relationships and being open to others. In proactively seeking out coalitions and connections and examining the new that emerges from this, my practice is similarly supported and strengthened.

My commitment to using found, ephemeral and repurposed materials and to working with them by hand helps protect and conserve natural resources. The work I produce is often transient and materials used are often recycled from one work to another. Making art in this way has contributed significantly to my being able to sustain a practice without access to large premises or funding. At the same time, it puts sustainability at the centre of the work for all to experience.

Decisions about how and where to share and show work are influenced by the carbon emissions involved but it is primarily using digital communication that I have been able to effectively sustain this integral aspect of my practice.

A love of the land we stand on, connecting with the beauty of the short-lived, feelings of radical hope and unquestioning faith in the process…all propel me to continue ‘practising’. I am bound to this – and to the challenge of communicating real-life uncertainty.

[1]Brian Massumi, The Politics of Affect, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), p. ix.

Find out more about Fiona’s practice on her website and follow her on Instagram.

Fiona was interviewed in January 2024.

All images are courtesy of the artist.